36 KiB

| title | teaser | menu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| spaCy 101: Everything you need to know | The most important concepts, explained in simple terms |

|

Whether you're new to spaCy, or just want to brush up on some NLP basics and implementation details – this page should have you covered. Each section will explain one of spaCy's features in simple terms and with examples or illustrations. Some sections will also reappear across the usage guides as a quick introduction.

Help us improve the docs

Did you spot a mistake or come across explanations that are unclear? We always appreciate improvement suggestions or pull requests. You can find a "Suggest edits" link at the bottom of each page that points you to the source.

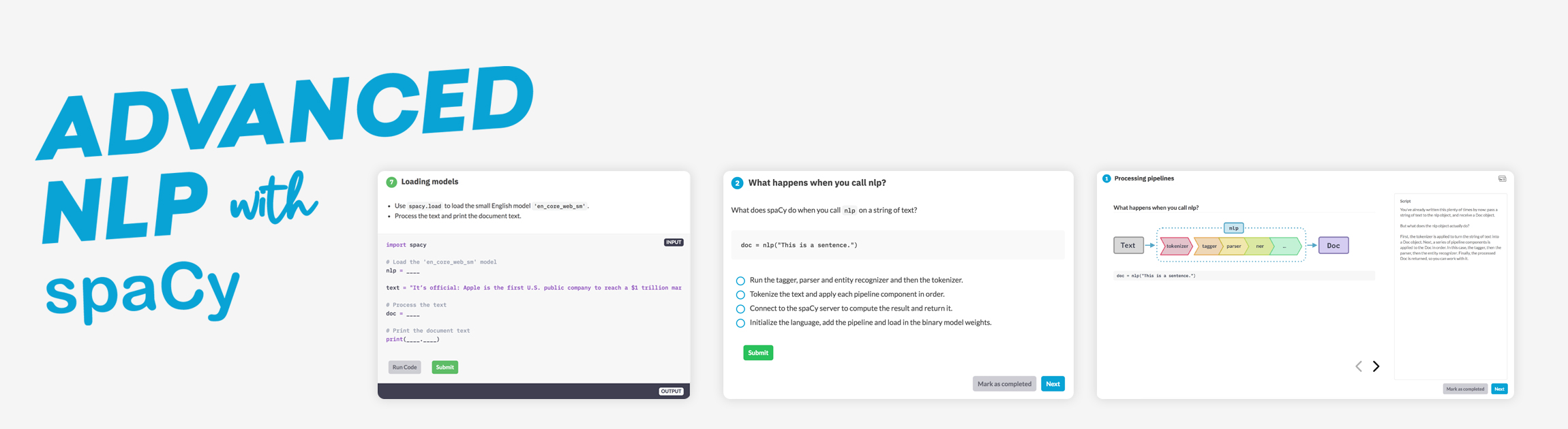

In this course you'll learn how to use spaCy to build advanced natural language understanding systems, using both rule-based and machine learning approaches. It includes 55 exercises featuring interactive coding practice, multiple-choice questions and slide decks.

Start the course

What's spaCy?

spaCy is a free, open-source library for advanced Natural Language Processing (NLP) in Python.

If you're working with a lot of text, you'll eventually want to know more about it. For example, what's it about? What do the words mean in context? Who is doing what to whom? What companies and products are mentioned? Which texts are similar to each other?

spaCy is designed specifically for production use and helps you build applications that process and "understand" large volumes of text. It can be used to build information extraction or natural language understanding systems, or to pre-process text for deep learning.

- Features

- Linguistic annotations

- Tokenization

- POS tags and dependencies

- Named entities

- Word vectors and similarity

- Pipelines

- Vocab, hashes and lexemes

- Serialization

- Training

- Language data

- Lightning tour

- Architecture

- Community & FAQ

What spaCy isn't

-

spaCy is not a platform or "an API". Unlike a platform, spaCy does not provide a software as a service, or a web application. It's an open-source library designed to help you build NLP applications, not a consumable service.

-

spaCy is not an out-of-the-box chat bot engine. While spaCy can be used to power conversational applications, it's not designed specifically for chat bots, and only provides the underlying text processing capabilities.

-

spaCy is not research software. It's built on the latest research, but it's designed to get things done. This leads to fairly different design decisions than NLTK or CoreNLP, which were created as platforms for teaching and research. The main difference is that spaCy is integrated and opinionated. spaCy tries to avoid asking the user to choose between multiple algorithms that deliver equivalent functionality. Keeping the menu small lets spaCy deliver generally better performance and developer experience.

-

spaCy is not a company. It's an open-source library. Our company publishing spaCy and other software is called Explosion AI.

Features

In the documentation, you'll come across mentions of spaCy's features and capabilities. Some of them refer to linguistic concepts, while others are related to more general machine learning functionality.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Tokenization | Segmenting text into words, punctuations marks etc. |

| Part-of-speech (POS) Tagging | Assigning word types to tokens, like verb or noun. |

| Dependency Parsing | Assigning syntactic dependency labels, describing the relations between individual tokens, like subject or object. |

| Lemmatization | Assigning the base forms of words. For example, the lemma of "was" is "be", and the lemma of "rats" is "rat". |

| Sentence Boundary Detection (SBD) | Finding and segmenting individual sentences. |

| Named Entity Recognition (NER) | Labelling named "real-world" objects, like persons, companies or locations. |

| Entity Linking (EL) | Disambiguating textual entities to unique identifiers in a Knowledge Base. |

| Similarity | Comparing words, text spans and documents and how similar they are to each other. |

| Text Classification | Assigning categories or labels to a whole document, or parts of a document. |

| Rule-based Matching | Finding sequences of tokens based on their texts and linguistic annotations, similar to regular expressions. |

| Training | Updating and improving a statistical model's predictions. |

| Serialization | Saving objects to files or byte strings. |

Statistical models

While some of spaCy's features work independently, others require statistical models to be loaded, which enable spaCy to predict linguistic annotations – for example, whether a word is a verb or a noun. spaCy currently offers statistical models for a variety of languages, which can be installed as individual Python modules. Models can differ in size, speed, memory usage, accuracy and the data they include. The model you choose always depends on your use case and the texts you're working with. For a general-purpose use case, the small, default models are always a good start. They typically include the following components:

- Binary weights for the part-of-speech tagger, dependency parser and named entity recognizer to predict those annotations in context.

- Lexical entries in the vocabulary, i.e. words and their context-independent attributes like the shape or spelling.

- Data files like lemmatization rules and lookup tables.

- Word vectors, i.e. multi-dimensional meaning representations of words that let you determine how similar they are to each other.

- Configuration options, like the language and processing pipeline settings, to put spaCy in the correct state when you load in the model.

Linguistic annotations

spaCy provides a variety of linguistic annotations to give you insights into a text's grammatical structure. This includes the word types, like the parts of speech, and how the words are related to each other. For example, if you're analyzing text, it makes a huge difference whether a noun is the subject of a sentence, or the object – or whether "google" is used as a verb, or refers to the website or company in a specific context.

Loading models

$ python -m spacy download en_core_web_sm >>> import spacy >>> nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

Once you've downloaded and installed a model, you can load it

via spacy.load(). This will return a Language

object containing all components and data needed to process text. We usually

call it nlp. Calling the nlp object on a string of text will return a

processed Doc:

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("Apple is looking at buying U.K. startup for $1 billion")

for token in doc:

print(token.text, token.pos_, token.dep_)

Even though a Doc is processed – e.g. split into individual words and

annotated – it still holds all information of the original text, like

whitespace characters. You can always get the offset of a token into the

original string, or reconstruct the original by joining the tokens and their

trailing whitespace. This way, you'll never lose any information when processing

text with spaCy.

Tokenization

import Tokenization101 from 'usage/101/_tokenization.md'

To learn more about how spaCy's tokenization rules work in detail, how to customize and replace the default tokenizer and how to add language-specific data, see the usage guides on adding languages and customizing the tokenizer.

Part-of-speech tags and dependencies

import PosDeps101 from 'usage/101/_pos-deps.md'

To learn more about part-of-speech tagging and rule-based morphology, and how to navigate and use the parse tree effectively, see the usage guides on part-of-speech tagging and using the dependency parse.

Named Entities

import NER101 from 'usage/101/_named-entities.md'

To learn more about entity recognition in spaCy, how to add your own entities to a document and how to train and update the entity predictions of a model, see the usage guides on named entity recognition and training the named entity recognizer.

Word vectors and similarity

import Vectors101 from 'usage/101/_vectors-similarity.md'

To learn more about word vectors, how to customize them and how to load your own vectors into spaCy, see the usage guide on using word vectors and semantic similarities.

Pipelines

import Pipelines101 from 'usage/101/_pipelines.md'

To learn more about how processing pipelines work in detail, how to enable and disable their components, and how to create your own, see the usage guide on language processing pipelines.

Vocab, hashes and lexemes

Whenever possible, spaCy tries to store data in a vocabulary, the

Vocab, that will be shared by multiple documents. To save

memory, spaCy also encodes all strings to hash values – in this case for

example, "coffee" has the hash 3197928453018144401. Entity labels like "ORG"

and part-of-speech tags like "VERB" are also encoded. Internally, spaCy only

"speaks" in hash values.

- Token: A word, punctuation mark etc. in context, including its attributes, tags and dependencies.

- Lexeme: A "word type" with no context. Includes the word shape and flags, e.g. if it's lowercase, a digit or punctuation.

- Doc: A processed container of tokens in context.

- Vocab: The collection of lexemes.

- StringStore: The dictionary mapping hash values to strings, for example

3197928453018144401→ "coffee".

If you process lots of documents containing the word "coffee" in all kinds of

different contexts, storing the exact string "coffee" every time would take up

way too much space. So instead, spaCy hashes the string and stores it in the

StringStore. You can think of the StringStore as a

lookup table that works in both directions – you can look up a string to get

its hash, or a hash to get its string:

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("I love coffee")

print(doc.vocab.strings["coffee"]) # 3197928453018144401

print(doc.vocab.strings[3197928453018144401]) # 'coffee'

What does 'L' at the end of a hash mean?

If you return a hash value in the Python 2 interpreter, it'll show up as

3197928453018144401L. TheLjust means "long integer" – it's not actually a part of the hash value.

Now that all strings are encoded, the entries in the vocabulary don't need to

include the word text themselves. Instead, they can look it up in the

StringStore via its hash value. Each entry in the vocabulary, also called

Lexeme, contains the context-independent information about

a word. For example, no matter if "love" is used as a verb or a noun in some

context, its spelling and whether it consists of alphabetic characters won't

ever change. Its hash value will also always be the same.

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("I love coffee")

for word in doc:

lexeme = doc.vocab[word.text]

print(lexeme.text, lexeme.orth, lexeme.shape_, lexeme.prefix_, lexeme.suffix_,

lexeme.is_alpha, lexeme.is_digit, lexeme.is_title, lexeme.lang_)

- Text: The original text of the lexeme.

- Orth: The hash value of the lexeme.

- Shape: The abstract word shape of the lexeme.

- Prefix: By default, the first letter of the word string.

- Suffix: By default, the last three letters of the word string.

- is alpha: Does the lexeme consist of alphabetic characters?

- is digit: Does the lexeme consist of digits?

| Text | Orth | Shape | Prefix | Suffix | is_alpha | is_digit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 4690420944186131903 |

X |

I | I | True |

False |

| love | 3702023516439754181 |

xxxx |

l | ove | True |

False |

| coffee | 3197928453018144401 |

xxxx |

c | fee | True |

False |

The mapping of words to hashes doesn't depend on any state. To make sure each value is unique, spaCy uses a hash function to calculate the hash based on the word string. This also means that the hash for "coffee" will always be the same, no matter which model you're using or how you've configured spaCy.

However, hashes cannot be reversed and there's no way to resolve

3197928453018144401 back to "coffee". All spaCy can do is look it up in the

vocabulary. That's why you always need to make sure all objects you create have

access to the same vocabulary. If they don't, spaCy might not be able to find

the strings it needs.

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

from spacy.tokens import Doc

from spacy.vocab import Vocab

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("I love coffee") # Original Doc

print(doc.vocab.strings["coffee"]) # 3197928453018144401

print(doc.vocab.strings[3197928453018144401]) # 'coffee' 👍

empty_doc = Doc(Vocab()) # New Doc with empty Vocab

# empty_doc.vocab.strings[3197928453018144401] will raise an error :(

empty_doc.vocab.strings.add("coffee") # Add "coffee" and generate hash

print(empty_doc.vocab.strings[3197928453018144401]) # 'coffee' 👍

new_doc = Doc(doc.vocab) # Create new doc with first doc's vocab

print(new_doc.vocab.strings[3197928453018144401]) # 'coffee' 👍

If the vocabulary doesn't contain a string for 3197928453018144401, spaCy will

raise an error. You can re-add "coffee" manually, but this only works if you

actually know that the document contains that word. To prevent this problem,

spaCy will also export the Vocab when you save a Doc or nlp object. This

will give you the object and its encoded annotations, plus the "key" to decode

it.

Knowledge Base

To support the entity linking task, spaCy stores external knowledge in a

KnowledgeBase. The knowledge base (KB) uses the Vocab to store

its data efficiently.

- Mention: A textual occurrence of a named entity, e.g. 'Miss Lovelace'.

- KB ID: A unique identifier referring to a particular real-world concept, e.g. 'Q7259'.

- Alias: A plausible synonym or description for a certain KB ID, e.g. 'Ada Lovelace'.

- Prior probability: The probability of a certain mention resolving to a certain KB ID, prior to knowing anything about the context in which the mention is used.

- Entity vector: A pretrained word vector capturing the entity description.

A knowledge base is created by first adding all entities to it. Next, for each potential mention or alias, a list of relevant KB IDs and their prior probabilities is added. The sum of these prior probabilities should never exceed 1 for any given alias.

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

from spacy.kb import KnowledgeBase

# load the model and create an empty KB

nlp = spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

kb = KnowledgeBase(vocab=nlp.vocab, entity_vector_length=3)

# adding entities

kb.add_entity(entity="Q1004791", freq=6, entity_vector=[0, 3, 5])

kb.add_entity(entity="Q42", freq=342, entity_vector=[1, 9, -3])

kb.add_entity(entity="Q5301561", freq=12, entity_vector=[-2, 4, 2])

# adding aliases

kb.add_alias(alias="Douglas", entities=["Q1004791", "Q42", "Q5301561"], probabilities=[0.6, 0.1, 0.2])

kb.add_alias(alias="Douglas Adams", entities=["Q42"], probabilities=[0.9])

print()

print("Number of entities in KB:",kb.get_size_entities()) # 3

print("Number of aliases in KB:", kb.get_size_aliases()) # 2

Candidate generation

Given a textual entity, the Knowledge Base can provide a list of plausible

candidates or entity identifiers. The EntityLinker will

take this list of candidates as input, and disambiguate the mention to the most

probable identifier, given the document context.

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

from spacy.kb import KnowledgeBase

nlp = spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

kb = KnowledgeBase(vocab=nlp.vocab, entity_vector_length=3)

# adding entities

kb.add_entity(entity="Q1004791", freq=6, entity_vector=[0, 3, 5])

kb.add_entity(entity="Q42", freq=342, entity_vector=[1, 9, -3])

kb.add_entity(entity="Q5301561", freq=12, entity_vector=[-2, 4, 2])

# adding aliases

kb.add_alias(alias="Douglas", entities=["Q1004791", "Q42", "Q5301561"], probabilities=[0.6, 0.1, 0.2])

candidates = kb.get_candidates("Douglas")

for c in candidates:

print(" ", c.entity_, c.prior_prob, c.entity_vector)

Serialization

import Serialization101 from 'usage/101/_serialization.md'

To learn more about how to save and load your own models, see the usage guide on saving and loading.

Training

import Training101 from 'usage/101/_training.md'

To learn more about training and updating models, how to create training data and how to improve spaCy's named entity recognition models, see the usage guides on training.

Language data

import LanguageData101 from 'usage/101/_language-data.md'

To learn more about the individual components of the language data and how to add a new language to spaCy in preparation for training a language model, see the usage guide on adding languages.

Lightning tour

The following examples and code snippets give you an overview of spaCy's functionality and its usage.

Install models and process text

python -m spacy download en_core_web_sm

python -m spacy download de_core_news_sm

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("Hello, world. Here are two sentences.")

print([t.text for t in doc])

nlp_de = spacy.load("de_core_news_sm")

doc_de = nlp_de("Ich bin ein Berliner.")

print([t.text for t in doc_de])

API: spacy.load() Usage:

Models, spaCy 101

Get tokens, noun chunks & sentences

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("Peach emoji is where it has always been. Peach is the superior "

"emoji. It's outranking eggplant 🍑 ")

print(doc[0].text) # 'Peach'

print(doc[1].text) # 'emoji'

print(doc[-1].text) # '🍑'

print(doc[17:19].text) # 'outranking eggplant'

noun_chunks = list(doc.noun_chunks)

print(noun_chunks[0].text) # 'Peach emoji'

sentences = list(doc.sents)

assert len(sentences) == 3

print(sentences[1].text) # 'Peach is the superior emoji.'

API: Doc, Token Usage:

spaCy 101

Get part-of-speech tags and flags

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("Apple is looking at buying U.K. startup for $1 billion")

apple = doc[0]

print("Fine-grained POS tag", apple.pos_, apple.pos)

print("Coarse-grained POS tag", apple.tag_, apple.tag)

print("Word shape", apple.shape_, apple.shape)

print("Alphanumeric characters?", apple.is_alpha)

print("Punctuation mark?", apple.is_punct)

billion = doc[10]

print("Digit?", billion.is_digit)

print("Like a number?", billion.like_num)

print("Like an email address?", billion.like_email)

API: Token Usage:

Part-of-speech tagging

Use hash values for any string

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("I love coffee")

coffee_hash = nlp.vocab.strings["coffee"] # 3197928453018144401

coffee_text = nlp.vocab.strings[coffee_hash] # 'coffee'

print(coffee_hash, coffee_text)

print(doc[2].orth, coffee_hash) # 3197928453018144401

print(doc[2].text, coffee_text) # 'coffee'

beer_hash = doc.vocab.strings.add("beer") # 3073001599257881079

beer_text = doc.vocab.strings[beer_hash] # 'beer'

print(beer_hash, beer_text)

unicorn_hash = doc.vocab.strings.add("🦄") # 18234233413267120783

unicorn_text = doc.vocab.strings[unicorn_hash] # '🦄'

print(unicorn_hash, unicorn_text)

API: StringStore Usage:

Vocab, hashes and lexemes 101

Recognize and update named entities

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

from spacy.tokens import Span

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("San Francisco considers banning sidewalk delivery robots")

for ent in doc.ents:

print(ent.text, ent.start_char, ent.end_char, ent.label_)

doc = nlp("FB is hiring a new VP of global policy")

doc.ents = [Span(doc, 0, 1, label="ORG")]

for ent in doc.ents:

print(ent.text, ent.start_char, ent.end_char, ent.label_)

Usage: Named entity recognition

Train and update neural network models {#lightning-tour-training"}

import spacy

import random

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

train_data = [("Uber blew through $1 million", {"entities": [(0, 4, "ORG")]})]

other_pipes = [pipe for pipe in nlp.pipe_names if pipe != "ner"]

with nlp.disable_pipes(*other_pipes):

optimizer = nlp.begin_training()

for i in range(10):

random.shuffle(train_data)

for text, annotations in train_data:

nlp.update([text], [annotations], sgd=optimizer)

nlp.to_disk("/model")

API: Language.update Usage:

Training spaCy's statistical models

Visualize a dependency parse and named entities in your browser

Output

from spacy import displacy

doc_dep = nlp("This is a sentence.")

displacy.serve(doc_dep, style="dep")

doc_ent = nlp("When Sebastian Thrun started working on self-driving cars at Google "

"in 2007, few people outside of the company took him seriously.")

displacy.serve(doc_ent, style="ent")

API: displacy Usage:

Visualizers

Get word vectors and similarity

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_md")

doc = nlp("Apple and banana are similar. Pasta and hippo aren't.")

apple = doc[0]

banana = doc[2]

pasta = doc[6]

hippo = doc[8]

print("apple <-> banana", apple.similarity(banana))

print("pasta <-> hippo", pasta.similarity(hippo))

print(apple.has_vector, banana.has_vector, pasta.has_vector, hippo.has_vector)

For the best results, you should run this example using the

en_vectors_web_lg model (currently not

available in the live demo).

Usage: Word vectors and similarity

Simple and efficient serialization

import spacy

from spacy.tokens import Doc

from spacy.vocab import Vocab

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

customer_feedback = open("customer_feedback_627.txt").read()

doc = nlp(customer_feedback)

doc.to_disk("/tmp/customer_feedback_627.bin")

new_doc = Doc(Vocab()).from_disk("/tmp/customer_feedback_627.bin")

API: Language, Doc Usage:

Saving and loading models

Match text with token rules

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

from spacy.matcher import Matcher

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

matcher = Matcher(nlp.vocab)

def set_sentiment(matcher, doc, i, matches):

doc.sentiment += 0.1

pattern1 = [{"ORTH": "Google"}, {"ORTH": "I"}, {"ORTH": "/"}, {"ORTH": "O"}]

pattern2 = [[{"ORTH": emoji, "OP": "+"}] for emoji in ["😀", "😂", "🤣", "😍"]]

matcher.add("GoogleIO", None, pattern1) # Match "Google I/O" or "Google i/o"

matcher.add("HAPPY", set_sentiment, *pattern2) # Match one or more happy emoji

doc = nlp("A text about Google I/O 😀😀")

matches = matcher(doc)

for match_id, start, end in matches:

string_id = nlp.vocab.strings[match_id]

span = doc[start:end]

print(string_id, span.text)

print("Sentiment", doc.sentiment)

API: Matcher Usage:

Rule-based matching

Minibatched stream processing

texts = ["One document.", "...", "Lots of documents"]

# .pipe streams input, and produces streaming output

iter_texts = (texts[i % 3] for i in range(100000000))

for i, doc in enumerate(nlp.pipe(iter_texts, batch_size=50)):

assert doc.is_parsed

if i == 100:

break

Get syntactic dependencies

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("When Sebastian Thrun started working on self-driving cars at Google "

"in 2007, few people outside of the company took him seriously.")

dep_labels = []

for token in doc:

while token.head != token:

dep_labels.append(token.dep_)

token = token.head

print(dep_labels)

API: Token Usage:

Using the dependency parse

Export to numpy arrays

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

from spacy.attrs import ORTH, LIKE_URL

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("Check out https://spacy.io")

for token in doc:

print(token.text, token.orth, token.like_url)

attr_ids = [ORTH, LIKE_URL]

doc_array = doc.to_array(attr_ids)

print(doc_array.shape)

print(len(doc), len(attr_ids))

assert doc[0].orth == doc_array[0, 0]

assert doc[1].orth == doc_array[1, 0]

assert doc[0].like_url == doc_array[0, 1]

assert list(doc_array[:, 1]) == [t.like_url for t in doc]

print(list(doc_array[:, 1]))

Calculate inline markup on original string

### {executable="true"}

import spacy

def put_spans_around_tokens(doc):

"""Here, we're building a custom "syntax highlighter" for

part-of-speech tags and dependencies. We put each token in a

span element, with the appropriate classes computed. All whitespace is

preserved, outside of the spans. (Of course, HTML will only display

multiple whitespace if enabled – but the point is, no information is lost

and you can calculate what you need, e.g. <br />, <p> etc.)

"""

output = []

html = '<span class="{classes}">{word}</span>{space}'

for token in doc:

if token.is_space:

output.append(token.text)

else:

classes = "pos-{} dep-{}".format(token.pos_, token.dep_)

output.append(html.format(classes=classes, word=token.text, space=token.whitespace_))

string = "".join(output)

string = string.replace("\\n", "")

string = string.replace("\\t", " ")

return "<pre>{}</pre>".format(string)

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp("This is a test.\\n\\nHello world.")

html = put_spans_around_tokens(doc)

print(html)

Architecture

import Architecture101 from 'usage/101/_architecture.md'

Community & FAQ

We're very happy to see the spaCy community grow and include a mix of people from all kinds of different backgrounds – computational linguistics, data science, deep learning, research and more. If you'd like to get involved, below are some answers to the most important questions and resources for further reading.

Help, my code isn't working!

Bugs suck, and we're doing our best to continuously improve the tests and fix bugs as soon as possible. Before you submit an issue, do a quick search and check if the problem has already been reported. If you're having installation or loading problems, make sure to also check out the troubleshooting guide. Help with spaCy is available via the following platforms:

How do I know if something is a bug?

Of course, it's always hard to know for sure, so don't worry – we're not going to be mad if a bug report turns out to be a typo in your code. As a simple rule, any C-level error without a Python traceback, like a segmentation fault or memory error, is always a spaCy bug.

Because models are statistical, their performance will never be perfect. However, if you come across patterns that might indicate an underlying issue, please do file a report. Similarly, we also care about behaviors that contradict our docs.

- Stack Overflow: Usage questions and everything related to problems with your specific code. The Stack Overflow community is much larger than ours, so if your problem can be solved by others, you'll receive help much quicker.

- Gitter chat: General discussion about spaCy, meeting other community members and exchanging tips, tricks and best practices.

- GitHub issue tracker: Bug reports and improvement suggestions, i.e. everything that's likely spaCy's fault. This also includes problems with the models beyond statistical imprecisions, like patterns that point to a bug.

Please understand that we won't be able to provide individual support via email. We also believe that help is much more valuable if it's shared publicly, so that more people can benefit from it. If you come across an issue and you think you might be able to help, consider posting a quick update with your solution. No matter how simple, it can easily save someone a lot of time and headache – and the next time you need help, they might repay the favor.

How can I contribute to spaCy?

You don't have to be an NLP expert or Python pro to contribute, and we're happy

to help you get started. If you're new to spaCy, a good place to start is the

help wanted (easy) label

on GitHub, which we use to tag bugs and feature requests that are easy and

self-contained. We also appreciate contributions to the docs – whether it's

fixing a typo, improving an example or adding additional explanations. You'll

find a "Suggest edits" link at the bottom of each page that points you to the

source.

Another way of getting involved is to help us improve the language data – especially if you happen to speak one of the languages currently in alpha support. Even adding simple tokenizer exceptions, stop words or lemmatizer data can make a big difference. It will also make it easier for us to provide a statistical model for the language in the future. Submitting a test that documents a bug or performance issue, or covers functionality that's especially important for your application is also very helpful. This way, you'll also make sure we never accidentally introduce regressions to the parts of the library that you care about the most.

For more details on the types of contributions we're looking for, the code conventions and other useful tips, make sure to check out the contributing guidelines.

spaCy adheres to the Contributor Covenant Code of Conduct. By participating, you are expected to uphold this code.

I've built something cool with spaCy – how can I get the word out?

First, congrats – we'd love to check it out! When you share your project on Twitter, don't forget to tag @spacy_io so we don't miss it. If you think your project would be a good fit for the spaCy Universe, feel free to submit it! Tutorials are also incredibly valuable to other users and a great way to get exposure. So we strongly encourage writing up your experiences, or sharing your code and some tips and tricks on your blog. Since our website is open-source, you can add your project or tutorial by making a pull request on GitHub.

If you would like to use the spaCy logo on your site, please get in touch and ask us first. However, if you want to show support and tell others that your project is using spaCy, you can grab one of our spaCy badges here:

<img src={https://img.shields.io/badge/built%20with-spaCy-09a3d5.svg} />

[](https://spacy.io)

<img src={https://img.shields.io/badge/made%20with%20❤%20and-spaCy-09a3d5.svg}

/>

[](https://spacy.io)